On Equal Terms

John Haberin New York City

Summer Sculpture 2025

Temitayo Ogunbiyi must be flattered. For its fortieth birthday, the Isamu Noguchi Museum asks her to bring her art to the United States.

More impressive still, it invites her to enter on equal terms with Noguchi. She does not just get a gallery to show off their affinity. She exhibits alongside him, their work toe to toe and face to face. If you cannot quite say which of the old metaphors to apply, that is itself a tribute to what he brought to modern sculpture—and to what Ogunbiyi hopes for sculpture now.  This is not public sculpture, but New York summer sculpture all the same. If you have to head for Astoria, on the Queens waterfront, to see it, no sculptor is more open than Noguchi to those who look.

This is not public sculpture, but New York summer sculpture all the same. If you have to head for Astoria, on the Queens waterfront, to see it, no sculptor is more open than Noguchi to those who look.

Once again in 2025, public sculpture thrives on New York's great outdoors, in its many parks. It also thrives on leaving Manhattan for Ogunbiyi in the Noguchi Museum with Socrates Sculpture Park just two blocks away, as well as Torkwase Dyson in Brooklyn Bridge Park. For those not up to the challenge of Brooklyn and Queens, the options are greater still. Hunting them down is itself rewarding. They include Jennie C. Jones on the Met roof, Thaddeus Mosley in City Hall Park, David Q. Sheldon in Harlem Gardens, and Alma Allen on Park Avenue. But a Nigerian in Queens first.

Equal terms

Isamu Noguchi makes art far too responsive for a museum's customary divisions into galleries and rooms. The Noguchi Museum calls its divisions just "areas." Even with a map and the occasional wall label, you will find it hard to know where one area ends and the next begins. You might say the same, too, about borders to works of art, and Temitayo Ogunbiyi addresses them directly. Entering past the front desk brings you to the same old, same old—a selection of his work pretty much exactly where it was. The newcomer just adds some of her own.

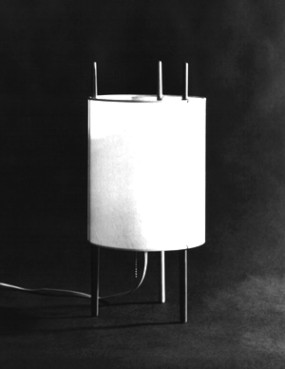

At first glance, the two do not have much obvious in common. Noguchi runs to massive objects resting firmly on the ground, obliterating the distinction between sculpture and its base. He works closely with materials like cast metal or carved stone, for coarse edges, a fine polish, or near uniform stippling. He rests content with the simplest of geometry or none at all. Ogunbiyi draws steel or copper rods into curves that start and end on the floor, before wrapping them in rope. Her meandering arches could pass for rope themselves, all set for rodeo tricks.

She is neither taking Noguchi as a model nor disdaining him, but rather making connections. Her rope might almost be tying them together, physically and visually, even as the work spills out past museum walls. In the process, their distinct styles start to look more and more alike. Noguchi turned eighty the year of her birth, in upstate New York in 1984, and did not have long to live. She moved to Philadelphia with her immigrant parents, from Jamaica and Nigeria, and has settled down in Lagos, Nigeria, a more populous city than New York. All the same, she might be thinking, "You Will Wonder If We Would Have Been Friends."

I quote the exhibition title, named for a watercolor with touches of pen. Her reptilian curves appear flattened to the dimensions of paper—or to the ridges of a snail shell. She pays explicit homage by taking his shapes and materials as feet for sculptured curves as well. Like Noguchi, she makes no concessions to realism. Still, neither artist could mind if you describe sculpture in human or animal terms. It was, after all, once alive in the artist's hands.

It may have human purposes as well. Ogunbiyi has also worked in playground design, at once art, architecture, and the molding of space itself. She says that she took an interest watching her daughter at play in Africa, but she must have known its interest for Noguchi as well. It brings out a shared sense of play, for all his monumentality and stillness, like that of his planned memorial to Hiroshima. The garden museum really is a privileged enclave and a place for contemplation, quite as much as the reopened Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue. If it has humbler and dirtier origins, with industry and Costco still across the street, Noguchi valued the everyday.

Ogunbiyi does bring a playground to Queens—not to the waterfront like Socrates Sculpture Park nearby, but right inside. She gets a small, separate room after all for just that. It looks much like the rest of her work, with three arches and two stone chairs. Kids could run free here, if not for the run of the show, but it might be tough. They could go for pull-ups using her arches, and never mind if they fail. Despite a thin fabric layer, parents would find hard seating as well. Such is the price of freedom.

Really minimal?

For once, heading outdoors for real, it makes sense to start on New York's summer sculpture with the Met roof. True, it, too, is not public sculpture in the city's abundant parks, no more than Ogunbiyi, but the view brings it close enough—especially with the roof about to close to bring it fully into the Met, as part of a redesign of its modern and contemporary wing. It has also been each year's first to open. With her interest in music, you might say that Jennie C. Jones set the tone for everything to come, as I explain further in a separate review.  In particular, it had me asking about the place of Minimalism in sculpture a mere half century after artists and critics alike pretty much moved on. Sure enough, Edra Soto and Torkwase Dyson could pass for the real thing.

In particular, it had me asking about the place of Minimalism in sculpture a mere half century after artists and critics alike pretty much moved on. Sure enough, Edra Soto and Torkwase Dyson could pass for the real thing.

Both adopt industrial materials, with the warm browns of rusted steel. Both, too, work on a scale a bit larger than life, to invite viewers into the work. You can see through Soto's gates to others out for a stroll with Central Park behind them. If, like Jones, it is not quite art in the parks, it is this year's commission for the park's southeast entrance, across from the Plaza Hotel, and it welcomes the view. Dyson, in turn, creates a pavilion, with seating. The closer you get, though, the more it opens to the sky.

Both works do the unexpected for Minimalism, in accord with the eclectic "neo-Minimalism" common enough today. For such large, heavy sculpture, Soto's could pass for painting. It divides neatly into four panels, each a geometric abstraction. Slim metal rods radiate outward, forming a surface at their center that reflects sunlight. And their radiance tells a story, about crossing borders. They recall for Soto the wrought-iron screens outside homes in her native Puerto Rico, and they rest on terrazzo within the picture plane, as if decorative tiling had taken flight.

Where Soto calls her work Graft, grafted onto her adopted city, this is Dyson's Akua, meaning born on Wednesday, although I hesitate to ask why. Fresh off the 2024 Whitney Biennial, she has a lawn in Brooklyn Bridge Park, set back just far enough to make Brooklyn Heights, Dumbo, and the East River already distant memories. One can, though, see a shifting role for the work and its surroundings. What at first looks broad and solid, tapering in and out like the cooling tower of a nuclear reactor, reaches easily overhead. It also breaks up that much more clearly into metal beams with a circular opening above. A metal sheet on the ground could be the royal carpet inside.

Not that others can let go of Minimalism either, so long as they can run wild. Steve Tobin has his industrial roots, too, in more ways than one. His New York Roots began as piping before taking off in all directions exactly as the title would suggest. The half dozen works might have grown out of the ground here and there in the Garment District entirely on their own. Carl D'Alvia brings much the same party colors to the Upper West Side—and only a bit more restraint. His work, on the Broadway median strip, plays on its compact shapes and single colors. It keeps threatening to settle down into geometric or alphabetic form, mostly near subway stops, only to refuse the offer.

But enough of abstract art, whatever the story line. How about the real New York, where pigeons are ready to prey on whatever you can offer? The spur of the High Line, near West 30th Street, has a history now of single works, with Iván Argote. Like a white drone by Sam Durant not long ago, Argote is thinking in terms of motion, although he titles his work Dinosaur, as if it were well past its prime. Like a bare tree by Pamela Rosenkranz just last year, he is thinking, too, in terms of natural life. His oversize pigeon, while beautifully detailed, looks a trifle obvious all the same.

A softer bronze

When Melvin Edwards brought summer sculpture to City Hall Park, just one year ago, it seemed only fair to New York. A city of unmatched achievement and diversity deserved a black man of exceptional achievement. But that was the year of Covid-19 in the arts, when just soldiering on counted, and a pillar by Thaddeus Mosley towered over the scant crowds braving the art fairs. Now Mosley returns with the same dual commitment to Modernism and black America, and that dualism makes it shine, but its very nature has changed. When Edwards makes a point of welding and sculptural weight, he recalls both a slave's manacles and David Smith. When Mosley turns to bronze in the same park as Edwards before him, he gives modern art a longer history and a softer edge.

Just short of a hundred, Mosley has himself a history, and here he casts bronze after his own past sculpture in wood. Black abstraction has become a staple, and he should know. That whole time he has been living, working, and learning in Pennsylvania, between the Carnegie museums and steel country. His idea, though, of a city dweller is caught up in the woods. One could easily mistake his sculpture for wood at that, between its comforting brown and rounded surface. He takes care, he says, to retain the experience of differently kinds of trees as he gathers and cuts into them.

Sculpture for him also looks back all the way to Surrealism, with nested biomorphic shapes. Human forms peep out as dancers and pre-industrial actors rather than Smith's icons of postwar American labor. David Q. Sheldon prefers Smith's sharp edges overlaid and multiplied, typically with Smith's steel shine. Up in Harlem, at one entrance to St. Nicholas Park, this version is bright yellow. If that were not welcoming enough, Michel Bassompiere sets down bears on the Park Avenue South median strip. If that sounds more sentimental than Mosley and Sheldon combined, it is.

At least one sculpture park this summer had to do without summer sculpture. As plans tanked at the last minute and work promised online failed to appear, Socrates Sculpture Park fell back on its Socrates Annual, starting just days before summer itself bid its normal overhasty exit. Meanwhile Queens locals and others could settle for summer picnics, the view of Manhattan from Astoria, and scheduled performances by Pioneers Go East, a collective. It could be what they came for in the first place. Besides, they could always hold out for the emerging artists set for a colder New York. Better still, the park this year has boiled its selection down to just four contributors and the waterfront. That and New York City.

While I must defer a proper encounter to a later review, allow me to end in a more central location and on a more upscale note. Alma Allen starts her stroll along Park Avenue at 52nd Street, in the shadow of the great Seagram Building and within blocks of the Museum of Modern Art. No wonder she creates sculpture pared down to late Modernism. A variant on a tube snakes back on itself to end at the top, with a resting place for an equally glittering bronze ball. Further up on the avenue's median strip, self-closure has a change in spirit, but not in clarity and shine. There metal strips come from behind to land in what might be the sculpture's lap.

Has Minimalism become rough fabric or raw flesh? Either way, it retains a dedication to symmetry, mass, and shine. Come to think of it, that earlier ball could be a seed, and Allen's sculpture in the 2014 Whitney Biennial took the form of a giant nut. The works along the course of nearly a mile offer further variations on those themes, like the figure, headless but still gleaming, wrapping its arms around what could be a stack of waste baskets or an oil drum. An older man, fully formed and slightly daft, raises his cane in attack or defense. The poles of elegance and nature's wildness could stand for the entirety of summer sculpture. Like Allen, it goes first and foremost for charm.

Temitayo Ogunbiyi ran at the Isamu Noguchi Museum through November 2, 2025, Jennie C. Jones on the roof of The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 19, Edra Soto at the southeast corner of Central Park through August 24, Carl D'Alvia on Broadway on the Upper West Side through November 1, Iván Argote on the High Line through November 30, Thaddeus Mosley in City Hall Park through November 16, David Q. Sheldon beside St. Nicholas Park through October 30, and Alma Allen along Park Avenue through September 30. Torkwase Dyson ran in Brooklyn Bridge Park March 8, 2026, Steve Tobin at street level in the West 50s through February 28, Michel Bassompiere along Park Avenue South through May 11, and the Socrates Annual in Socrates Sculpture Park through April 6. I continue to follow summer sculpture as in past years going back to summer 2003.