Community and Commitment

John Haberin New York City

Consuelo Kanaga and Sheida Soleimani

New Photography 2025

People remember Consuelo Kanaga and Sheida Soleimani for their sense of community and commitment. I remember the lonely eye behind the camera and the pleasure of what they saw. Can either story bring them into the mainstream of modern photography and modern art, where Kanaga was years ago? Soleimani has dedicated her work to another kind of flight as well, of migratory birds, many suffering injury or disease. After so many years, can photography bring deliverance?

Wherever she went, Kanaga found a movement in which she could believe. She made a name for herself in San Francisco in Group f.64, but she left for New York in her twenties to hook up with Alfred Stieglitz, her friend and mentor, and to join the Photo League, a cooperative that cared as much about social as creative causes. The Brooklyn Museum opens her busy retrospective with a community at that.  A brief introduction sets her alongside an impressive roster of photographers, all of them women, who shared their progressive politics and took photographs of one another. You can see why Kanaga is known today mostly for portraiture, most notably of African Americans. Yet you may hardly notice she is there.

A brief introduction sets her alongside an impressive roster of photographers, all of them women, who shared their progressive politics and took photographs of one another. You can see why Kanaga is known today mostly for portraiture, most notably of African Americans. Yet you may hardly notice she is there.

Soleimani was born the same year as an emerging nation, a subject for "New Photography 2005" at MoMA as well. Neither event must have seemed auspicious. Iran declared itself an Islamic republic after taking Americans hostage and precipitating a global crisis. It had her parents among the many fearing for their lives. She spent her infancy in uncertainty and fear before the family's escape to America. She calls her survey at the International Center of Photography "Panjereh," which means both a passageway and a window in Farsi, but theirs is not its only record of passage.

Lonely community

As her show's title has it, Consuelo Kanaga was out to "Catch the Spirit"—the spirit of her sitters, the spirit of her times, and the spirit of the left. Yet the first image that may catch your eye as you enter is of lower Manhattan without a person in sight. It looks south with the Brooklyn Bridge nearly lost in a mist but light rippling down the water and spots of light piercing the morning air. She had an esthetics of control, from the large and then medium-format camera with which she began to her techniques of dodging, or burning a print with touches of light, and, every so often, touches by hand. Alfred Stieglitz, of course, had his own gallery, which enabled him to spread the word about modern art. And f.64 took its name from the sharpest setting on the camera back then, to capture every detail.

That small opening room itself suggests a dual or divided commitment. It includes Berenice Abbott and Imogen Cunningham, with their painterly photographs of the "new woman," as well as Tina Modotti, who made mostly portraits (and sat for many more), and Dorothea Lange, with her memorable images of poverty and the New Deal. Born in 1894 (of Swiss ancestry, her Spanish first name notwithstanding), Kanaga was still going strong enough to seek out the artist community in Taos in 1955. That same year she contributed to The Family of Man, the photo essay by Edward Steichen. She photographed a mother and her children, just as Lange's best-known image showed a migrant mother in 1936. She Is the Tree of Life to Them, Kanaga called it, when idealism still spread.

That division was not simply ambivalence, but a necessity. She started as a newspaper photographer, for the San Francisco Chronicle, but opened a portrait studio to make ends meet. Ironically, it has overshadowed everything else, enough to leave her all but forgotten. Even so, her style gives substance and unity to the whole. On the one hand, she contributed to The Daily Worker. On the other, she created purely abstract photography the year of her death, in 1978.

Not surprisingly, her portraits often run to creative types and to blacks. She found both in Langston Hughes, here at the center of the show's largest section. He poses in profile, meticulously dressed. But then her portraits have much the same bag of creative tricks when it comes to the common man or woman. She loves wide eyes, hands held to the sitter's cheeks, and shadows darkening a sitter's brow. She was asking to recognize a subject's dignity.

For all that, her commitments were as eclectic as ever, because the tree of life demands no less. She quickly switched to a smaller, more portable camera, bringing her artistry to small prints as well. Still, she was never a documentary photographer or street photographer, because she had no interest in spontaneity. She took to the rooftops, for a New Yorker's favorite sight, the multiplicity of exhaust vents, just as her view of lower Manhattan had no people and nowhere to stand. She still traveled, to North Africa and Venice, closing in on the basilica cathedral of San Marco. Naturally she prefers the intricacy of its architecture to the commonality of its public square.

She has paid a price for her poses. They can become predictable and perilously close to hokey. Still, even the sentiment is heartfelt, and it can never erase her eclecticism and commitment. Are the folds covering a woman rags or flowers? Are young women leaning toward each other in seeming amazement strangers or twins? For a moment, the only spirit that matters is theirs.

Photography in flight

Sheida Soleimani probably cannot remember much of Iran, but everything she does is infused with memory. She knows that passage did not come easily. Her parents had to rely on separate escape routes, one more circuitous than the other, battered suitcases, and two sets of plants to make the adopted country feel like home—and she pictures them all separately, too. Even so, this is anything but documentary photography or photojournalism. In the print actually called Deliverance, her father rides on horseback, a Persian rug in place of a saddle. Elsewhere he sits on the same rug but on the floor, as if to have the best of both worlds, Islamic tradition and hipster yoga.

Husband and wife share their photographic stardom with all manner of actors, human and otherwise. Soleimani is at once a photographer, an activist, and a federally licensed wildlife rehabilitator. The connections are no more than puns, but her parents and the birds are painfully real. She describes subsets of her series as about OPEC, human rights abuses, reparations packages, geopolitical violence, and testimony to survivors. She calls her longest series "Ghostwriter" because it is their story as much as hers.  Never mind, though, for the only people are family, and there is no end of birds.

Never mind, though, for the only people are family, and there is no end of birds.

Birds may appear up close gripped by a healing hand or plopped down in the midst of chaos. It is a chaos at least partly of her own making. The confluence of humans and live animals may recall Surrealism, but think instead of Robert Rauschenberg and his stuffed goat. It looks more like Rauschenberg's combines and collaborations or today's collage and assemblage than Modernism's dream state. Cut blue squares and paper strips dismember the narrative and bring the image that much close to the layered surface. It is less about representation than coexistence.

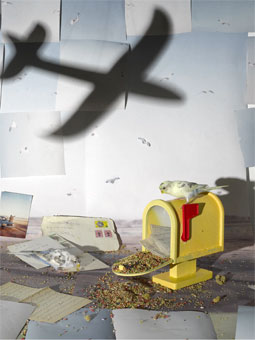

The very first work suggests the treachery of coexistence. A bird perches atop a mailbox filled with birdseed, as if the post office alone can no longer deliver. Well-worn letters lie near the same, and who is to say if their message has lost its urgency? The shadow of a plane hovers above as part of a rescue operation—unless it is an air assault or just a toy. Only a color snapshot pinned in the middle distance provides a glimpse of home. And yet this memory, too, is real.

For Soleimani, in the face of everything, the subject is dark, but her tone is caring and downright funny. For better or worse, she is just not a down person. She hangs the show against walls painted with comic-strip birds in a sketchy white and blue. More of them same sketches appear on paper within the photographs. Other handlers hold not birds but snakes, but they seem fully capable, and anyway they could all be loose paper models. Her parents are masked, while gesturing in pantomime, but it is all a game.

The curator, Elisabeth Sherman, includes only about forty works, leaving ICP's larger galleries to Edward Burtynsky. Yet it seems complete enough, because the installation and the photos themselves reach out across the space. The photos themselves, like the restaging of escape from Iran, reach out to one another. One image follows her to a safe house that once secured passages to freedom, with a glass chess set. Iran, it seems to say, has a past, but its future has only a few moves left. Whether Donald J. Trump can deny others a future is not up to her.

Four continents

Give the Museum of Modern Art credit. When it comes to photography, it is dedicated to covering the globe. If that sounds like a tall order, it takes the task little by little, a year at a time. "New Photography 2025" has just eleven photographers in four countries. As if to rub in its determination, they reside on four continents as well, a majority are women, and at least two are queer. Politics is the order of the day, and a collective identifies itself as the Nepal Picture Library.

Not that the successor to "New Photography 2013," "New Photography 2015," "New Photography 2018," or "New Photography 2023" has taken an in-depth look at the state of each nation, its allegiances, and its conflicts. Those sharing a country do not share so much as a museum room. They are, though, familiar enough in their political and artistic alliances. You have not seen all of this before, but you have seen a lot more you should. Most work large or with installations. It is provocative but not always enough.

Some simply declare their allegiances and little more. That picture library documents "the public lives of women," meaning in practice rallies and mass meetings. Sandra Blow papers a wall with "queer joy."  Gabrielle Garcia Steib photographs immigrants who live and work in New Orleans, many of them family, as the "spiritual border to the Caribbean." Not that documentary and social photography is a dead end. Lindokuhle Sobekwa belongs to the proud tradition of Magnum photos going back to Robert Capa, which to Sobekwa means scraps of legal documents in Johannesburg.

Gabrielle Garcia Steib photographs immigrants who live and work in New Orleans, many of them family, as the "spiritual border to the Caribbean." Not that documentary and social photography is a dead end. Lindokuhle Sobekwa belongs to the proud tradition of Magnum photos going back to Robert Capa, which to Sobekwa means scraps of legal documents in Johannesburg.

Some play on familiar genres and imagery. I felt for Sheelasha Rajbhandari, who treats her work as sculpture, mounting pixilated photographs on hand-made furniture. It demands, ever so earnestly, "To Be Free," "To Be Fluid," and "To Feel." It hardly has room amid the good cheer for The Agony of the New Bed. I shall just have to trust Lebohang Kganye that she evokes her late mother. A boy by Prasiit Sthapit borders on the cutes.

Some, to their credit, play on formula, but deliberately and forcefully. Official sources, they know, make telling use of it to wield dangerous authority. Gabrielle Goliath arranges frontal portraits like mug shots in a long row across two walls, facing miniature pink and blue beds. They are victims of domestic violence. Tania Franco Klein makes a point of dull places, elusively. Her "Subject Studies" include more than a hundred sitters—in cars, diners, bathrooms, and offices.

Some do bring the unexpected and make it their signature. L. Kasimu Harris takes to black-owned lounges, for lively activity and plenty of smiles. Sabelo Mlangeni photographs rural weddings in South Africa, everyone in white and seemingly no one at home. They might be ghosts. Renee Royale sticks to sandy rivers reduced to dirt roads, while Lake Verea (Francisca Rivero-Lake Cortina and Carla Verea Hernández) is still more devoid of life. The duo photograph what might be diners or sheer artifice in Mexico City. Titles speak of Mascarón Dorado and Hojas de Metal (or golden mask and plate-metal leaves).

I tried to think that I had touched the soul of a continent or of art. I tried not to be mostly bored. The real fascination may have come in how often their subjects grew together. Nepal could be as modern as New Orleans and as feminist as New York. Klein's interiors with in Mexico, all of them peopled, lie beyond glass and behind blinds, for a hot day or a steamy film. It is never easy to encompass the world.

Consuelo Kanaga ran at the Brooklyn Museum through August 3, 2025, Sheida Soleimani at the International Center of Photography through September 28. "New Photography 2025" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 17, 2026.